Dear readers,

Just over a year ago, I wrote a blog article with 11 Spanish words and phrases that would make you chuckle and/or scratch your skull when they translated into English.

I have since been compiling more Spanish words and phrases, picked up much the same way my parrot Frida picks up our diverse humanoid chatter. Hailing from all parts of the Spanish speaking world, you’ll find Hondurisms (often referred to as caliché), Spain and various novels from South America.

So, take your minds off corrupt politicians, global warming, terrorism, wars and misery, and enjoy a bit of Spanglish brain food.

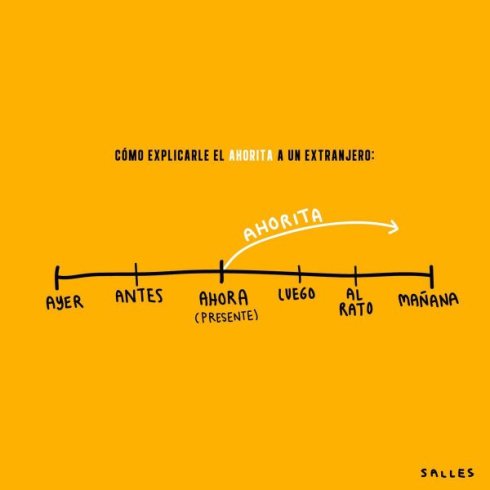

1. Ahorita

Diminutives are common in the idioma española. “What’s a diminutive?” you say. In short, it’s when you add ito/ita to a word to make subject/object smaller and/or more affectionate. Sometimes it can mean adding cito/cita or quita/quito depending on the last couple of letters of the base word. For instance, guapa (pronounced wapa) meaning good looking girlcan be transformed to guapita, becoming little good looking girl.

So, take ahorita, the base word being ahora meaningnow. You might be thinking how do I make the meaning of a word like ahora into something smaller and more affectionate without breaking the rules of relativity. Don’t worry, it perplexed me too when I first stepped foot in the Americas. But after little time, I was ahorita’ing it all over the place, which friends in Spain have noticed more than anyone. My amigos in Valencia claim I’ve forgotten their Castilian Spanish and been replaced with a Mexican hybrid.

Now, en ingles, means the present moment. Well, so does ahorita, but it also reaches into the future, as well as used to express the urgency of something happening that very second.

So, a sentence might look something like this:

Mira esta mamacita. Quiero besarla ahorita. (Look at the hot momma. I want to kiss her right now).

For a graphic explanation with a timeline, see the image below:

The meaning of ahorita

2. Palmear

This verb is pinched from a Mario Vargas Llosa novel, though I don’t hear it widely used in Honduras, nor did I in Spain, so I presume it’s used more in Peru; Vargas’s homeland. Then again, this context is not used in everyday, so it’s not that surprising I’ve not heard it much.

As you can see, the first four letters spell palm, which should trigger off a few ideas of its English translation. Yes, you might get a few funny looks if you offered to palm someone, interpreted as a possible veiled threat of violence or act of perversion. However, it actually means to pat or applaud someone, to be affectionate or congratulate a person; just a friendly palmear una espalda – pat on the back between acquaintances and/or friends.

3. Gustazazaso

A bit of a tongue twister, this, which could be incorporated into a drinking game! It is yet another word coming from a Mario Vargas Llosa novel although when I first laid eyes on it, dictionaries also had little or zero definitions.

However, a little investigation and common sense is always needed when coming across new vocabulary. The verb gustar is one of the first words to learn in the Spanish language, meaning to like, and you’re not wrong in thinking the two words are from the same family. The base form gustazo means take pleasure in something. Like ito/ita is used at the end of a word to minimise something, azo/aza is used to maximise, also known as an aumentative. So, gustazazaso means, as you may well have guessed, is to take great pleasure in something. Not in anything perverted, mind, but more so with someone you’ve not seen in a while.

4. Macizo

Quite simply one of my favourite caliché words, meaning cool. Not as in a cool beer kind of way, but a cool beer is cool way.

It’s pronounced ma-si-so with a stress on the middle syllable. I learned it at Casa Alianza and it has stuck to me ever since, although I did it pass it on to my brother, niece and nephew, who walk around saying the one word that epitomises street caliqué in a quaint village in Worcestershire, England.

How do we put this is a sentence?

You: Gané tres mil en el loto. (I won three thousand on the lottery).

Me: Macizo. Invítame a un six pack, pues. (Cool. Buy me a six pack of beer then).

5. Simón

Yes, this vastly popular name, which derives from the Hebrew name Simeon and featured in the Old Testament as one of the sons of Job, is also a street slang word from northern Mexico, which has filtered through to Honduras. It means ‘yes, okay’ in response or to acknowledge something that someone has said to you.

Why the name Simon, I don’t know. Whether it derives from a person of signficance called Simon in Tijuana or goes back to the Aztec languages, it is what it is. However, as it is pronounced sí mon,so taking a wild guess, sí could beyes and mon might be a mispronunciation of man, so it could actually mean a merge of yes, man.

I heard it for the first time from a kid in Casa Alianza who enjoyed confusing me in Spanish. Then last year I taught a young man called Yeison Rosado (who humorously called himself Mr. Pink and even wrote it on his exam paper. Also, rosado means pink for those not clear on the joke) who used to repeat it a loud after every time I’d said something. I eventually had to ban the word from the classroom because it drove me mental, so I figure the word simón is a must on this list. A banned word thanks to a man called Mr. Pink

Me: The present perfect in English includes the auxiliary verb have, followed by the past participle.

Mr. Pink: Simón.

6. A huevos

To beginners in Spanish, you probably recognise the word huevos from the dairy foods lesson. It means eggs after all (it can also be a slang term for a man’s eggs, if you see what I mean). A is the preposition to in English.

So the expression literally translates word for word as to eggs.

Yet the expression has nothing to do with eggs. In fact, it has a couple of different meanings depending on which country one lives in, although I’ll concentrate on the most common, which is something similar to simón i.e.to casually confirm a yes or acknowledge something someone’s said. It also depends on the tone, because it can be read as a sarcastic yes if the person before you said something unrealistic, a demand or basically untrue. I must add that it’s not the politest expression in the idioma española.

So, a non-sarcastic toned example might be:

Me: Alguien hizo un pedo. (Someone’s farted).

You: A huevos. (Yep).

A sarcastic toned example might be:

Me: Dame tres mil Lempiras. (Give me three thousand Lempiras).

You (with sarcastic facial expression): A huevos (Yeah, right).

7. Berenjenal

My Spanish teacher Ado taught me this one back at the language school Estudio Sampere in Madrid. She was a pretty young lady from Andalucía with dark hair, dark eyes, dark skin, the romantic fantasy that most foreign men think of when it comes to Spanish beauty. Funnily enough she had every male in the class (a few females too) hanging on her every word. What’s more, she was flamboyant and dynamic and had the raspy tongue of a truck driver, teaching us words she really shouldn’t have, which kept the class captivated.

And she used this word berenjenal to describe a classmate called John, who she also called el vikingo – the viking – because he hailed from Sweden, making poor old John from Malmö clown of the class. The thing is, John didn’t exactly help himself. He would spend all day partaking in an old Swedish tradition of sticking tiny pouches of tobacco called snus by his gums. He would do it during class, and one time Ado paused the class to say in a rather derogatory and patronising tone, ¡Que berenjenal! which left everyone in hysterics and John with a deflated ego.

So, what does berenjenal mean? It has two, actually. The first, and I’ll get this out the way quickly, is an eggplant field, and I don’t think Ado was calling John an eggplant field.

The second meaning is far more fitting, which is a coloquial noun for a mess/trouble in a Laurel and Hardy kind of way.

So, an example might be: en buen berenjenal nos hemos metido which roughly translates as what a fine mess we’ve got ourselves into.

8. Carpeta

In my CELTA course, we learned about false friends. In ESL talk, a false friend is a word that looks similar to a word in a different language but actually means something completely different. Embarazada means pregnant and sensible means sensitive for example. Well, carpeta is another false friend.

It actually means folder – either electronic or paper – rather than the carpet that goes on the floor.

So, you can say:

Mi perro comió mi carpeta. (My dog ate my folder).

It might confuse someone, however, if you say:

Mi perro hizo una caca en mi carpeta. (My dog did a poo on my folder).

9. Chamba

This is another very colloquial Honduran word, meaning job, although I vaguely remember the word meaning luck in Spain. There isn’t really an equivalent in English, and it isn’t the politest word for job, which no one told me before I embarrassed myself in front of a former employer during a performance review.

Boss: ¿Que tal el trabajo? (How is work?)

Me: Bueno, me gusta mi chamba . . .(Well, l like my job…)

Cue that look and a firm explanation that chamba is not an acceptable word to use in that particular work place. Luckily the boss understood that my faux pas wasn’t meant to offend and I still got a pay rise. Get in!

10. Dos veinte

I came across this expression about a year ago and it again involves our friend Yeison Rosado (aka. Mr Pink). You see, Mr Pink was sometimes a bit over enthusiastic about learning English, and while I encourage a positive attitude to learning, it could get bloody irritating when he talked over people, myself included.

Classmates then started calling him dos-veinte which led me into a word of confusion. To those not in the know, dos means two and veinte means twenty, so why on earth call someone two twenty?

Well, as it turns out, they were calling him something that pretty much describes him to a T. Dos veinte is used for someone who’s hyperactive or crazy, and with his blowing kisses at female classmates and drinking two cups of strong coffee during a one hour class, as I said, suits him down to a T. We always remember life’s interesting characters, don’t we!

You’re probably still thinking, how dos veinte mean hyperactive, though? Well, it applies to the plug sockets we use for the more powerful electrical appliances around the house i.e. fridges and cookers, etc.

An example might be:

Este majé es dos veinte. (This dude’s hyperactive).

11. Cae el veinte

That number veinte, again. A common number in Honduran expressions, it seems, although I think it is used throughout much of the Spanish speaking world. I like it. And again it was often used upon Mr. Pink.

Let me explain, cae comes from the verb caer which means to drop/to fall. If we put that together, drops the twenty, or in better English, the twenty drops, do you have any clues of its meaning in English? i.e. has the penny dropped yet? Funny that, because that is roughly how it translates: the penny drops.

Now I’m not sure how the penny drops gets its meaning in English, although I was told by someone here, but I can’t remember who, that cae el veinte comes from the time when public telephones were all the rage. You would let you 20 cent piece drop through the slot and you would be able to speak to whoever. This might be the origin but I might be wrong. However, the meaning is when someone tells you something but you don’t understand at first but you finally do through prompts and nudges.

Well Mr. Pink, for all his enthusiasm and infinite wisdom, often took a little while longer than classmates to understand how to use bits of vocabulary and grammar. To be fair, once the cae el veinte took place, he would use it more industrially and humorously than anyone I had met before.

Well, finally I have cae el veinte and realised 11 is just enough for you guys. Please give me feedback. If I have made a mistake or you have an alternative origin or meaning to the above words, let me know. Also, if you have any other Spanish words that might be of interest, leave a comment below.

Leave a comment