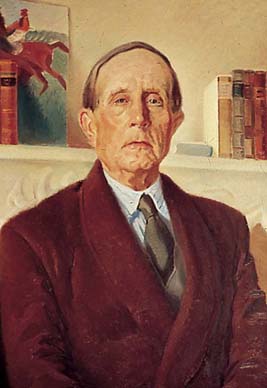

*Azorín (José Martínez Ruiz)

home

table of content

united architects – essays

table of content all sites

Azorín

Spanish, 1873–1967

Early in his career, José Martínez Ruiz adopted the pen name “Azorín,” under which he published novels, short stories, literary essays, plays, and countless articles in multiple turnof-the-century magazines and newspapers and, beginning in 1905, in the leading conservative Spanish newspaper, ABC. Azorín was one of a group of important Spanish writers who began publishing in the 1890s and attained their greatest achievements between 1900 and 1930. With Miguel de Unamuno, Antonio and Manuel Machado, Pío Baroja, Jacinto Benavente, Ramón del Valle-Inclán, and others, Azorín undertook a reexamination of the Spanish nation and the modern Spanish subject. Formerly, critics divided these writers and their contemporaries into two distinct groups, the “Modernistas” and the Generation of 1898, but recently the trend has been to collapse this distinction and to classify all as “Modernistas” and to link them more broadly with the Anglo-European Modernist project while allowing for cultural variations according to local historical and social conditions. Modernism represents a break with the traditional

sociosymbolic order and a search for new modes to express new experiences and perspectives.

Azorín’s essayistic writing demonstrates a Modernist rejection of the rationalist and scientific discourses that prevailed in the late 19th century and introduces a subjective, impressionistic, and highly poetic style. In some respects, it forges a link with the powerful but abbreviated production of the Romantic writer Mariano José de Larra, but in others it cultivates new modalities of writing in response to new modes of perception.

Azorín’s “essays” include both literary criticism and studies of the Spanish character and landscape; frequently these two categories blend in a single text. La ruta de don Quijote (1905; Don Quixote’s route) chronicles Azorín’s retracing of the wanderings of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza in La Mancha, with a continuous melding of literary reminiscence and contemporary commentary. Lecturas españolas (1912; Spanish readings), Clásicos y modernos (1913; Classics and moderns), and De Granada a Castelar (1922; From Granada to Castelar), among others, offer highly personal rereadings of classical and contemporary texts. In works such as Los pueblos (1905; The villages), España (1909; Spain), and Castilla (1912; Castile), literary criticism also appears, but in the service of a re-creation of the Spanish and, in particular, of the Castilian landscape, peoples, and history.

Like many of his contemporaries, Azorín distrusted official history and the 19thcentury belief in the objective reconstruction of facts; consequently, his texts repudiate the dispassionate tone, the emphasis on politics, and the reliance on government documents that characterize historical discourse of the period. In contrast, they foreground literary texts as a means to access the past and feature the lesser-known, sometimes anonymous figures of rural and small-town life as better guides to a reconstruction of previous periods than the biographies of notable public statesmen. In novels as well as essays, Azorín obsessively explores the theme of time and its passage, confronting the accelerated rhythm of modernity with a languorous exploration of the past as captured in the nonurban areas of Spain.

Azorín also breaks with literary and journalistic traditions in style and structure. His syntax represents a sharp departure from the heavily rhetorical style of 19th-century oratory, eschewing long sentences with multiple dependent clauses for short sentences with coordinate clauses. In keeping with a desire to bring the Spanish past into the present without sacrificing the cultural and linguistic specificity of Spain, Azorín and his contemporaries employ a rich lexicon that borrows freely from other languages while simultaneously resurrecting forgotten Spanish words drafted from specialized rural vocabularies.

Structurally, Azorín’s texts often defy traditional generic boundaries. Many of the “essays” incorporate techniques borrowed from narrative and poetry, and dialogue is a frequent visitor in Azorín’s essayistic writing. Castilla, one of his most widely-read publications, deliberately questions the established generic divisions through the careful construction of a collection of essays that move from conventional essay form through those incorporating poetic discourse, to those that take on a decidedly narrative form, and finally to the closing set of three that borrow strongly from dramatic techniques.

Furthermore, the final essays introduce yet another form through the use of ekphrasis and the introduction of visual art, thus questioning the borders of literature itself.

Many critics view Azorín’s experimentation with language and form as pure aestheticism, with no social or political implications. However, theorists of Modernism have refuted such a separation of content and form, and Azorín’s writing can benefit from a revision along the lines that have guided other rereadings of Anglo-European Modernist writers. Notwithstanding the emphasis on Castilian texts, landscape, and culture, Azorín’s publications insistently explore margins and boundaries, revising the canon, revisiting and reconstructing the past according to new visions, and denying the separation of art and life.

España, another important collection, demonstrates the insistence on multiple perspectives that cross traditional lines of separation and open up new possibilities for the perception of modern experience. The book combines the diachronic and the synchronic; the first 15 texts follow a chronological order, with each connected to a specific date, while the last 15 essays deal with contemporary issues and are devoid of historical references. Many of the essays emphasize the continuity of the past, while others foreground a disjointed historical evolution that places past and present in opposition.

Moreover, the marginalization of Spain, whether by its own choice or by foreign design, receives close scrutiny. Notwithstanding the title and the insistent examination of Spanish countryside, history, and culture, the text opens with an epigraph from Petrarch which appears in Italian and closes with an epilogue that was written in the French Pyrenees. Throughout the essays, the text speaker intrudes on the materials discussed in a constant reminder of the influence of the observer on what is observed and described, thus debunking any pretense of objectivity. Azorín’s essays thus reflect the Modernist impulse to develop new modes of writing and thinking in order to represent the complexities of modern experience.

MARY LEE BRETZ

Biography

Born José Martínez Ruiz, 8 June 1873 in Monóvar, Alicante. Also used the pseudonyms Cándido and Ahrimán. Studied at the Colegio de los Padres Escolapios, Yecla, 1881–88; law at the University of Valencia, from 1888. Moved to Madrid, 1896. Journalist for various newspapers, including ABC, El País (The country), El Progreso (Progress), and El Imparcial (The impartial). Elected deputy to the Spanish Parliament, 1907. Married Julia Guinda Urzanqui, 1908. Undersecretary for the Ministry of Public Instruction, 1917, 1919. Drama critic during the 1920s. Elected to the Royal Spanish Academy, 1914.

Columnist for La Nación (Buenos Aires), 1930–67. Lived in Paris, 1936–39. Died in Madrid, 2 March 1967.

Selected Writings

Essays and Related Prose

La crítica literaria en España, 1893

Moratín esbozo por Căndido, 1893

Buscapiés, 1894

Anarquistas literarios, 1895

Notas sociales, 1895

Literatura, 1896

Charivari., 1897

Soledades, 1898

La evolución de la crítica, 1899

La sociología criminal, 1899

Los hidalgos, 1900

El alma castellana, 1900

Los pueblos, 1905

La ruta de don Quijote, 1905

El político, 1908

España: Hombres y paisajes, 1909

La Cierva, 1910

Lecturas españolas, 1912

Castilla, 1912

Clásicos y modernos, 1913

Los valores literarios, 1913

Al margen de los clásicos, 1915

Rivas y Larra, 1916

Un pueblecito: Riofrío de Avila, 1916

Páginas escogidas, 1917

Entre España y Francia, 1917

El paisaje de España visto por los españoles, 1917

Madrid-Guía sentimental, 1918

Paris bombardeado, 1919

Fantasías y devaneos, 1920

Los dos Luises y otros ensayos, 1921

De Granada a Castelar, 1922

El chirrión de los políticos, 1923

Una hora de España, 1924; edited by José Montero Padilla, 1993

Racine y Molière, 1924

Los Quintero y otras páginas, 1925

Andando y pensando, 1929

Lope en silueta, 1935

Trasuntos de España, 1938

Valencia, 1941

Madrid, 1941

París, 1945

Memorias inmemoriales, 1946

Con permiso de los cervantistas, 1948

La cabeza de Castilla, 1950

Con bandera de Francia, 1950

Verano en Mallorca, 1952

El oasis de los clásicos, edited by J.García Marcada, 1952

El cine y el momento, 1953

El efímero cine, 1955

El pasado, 1955

Agenda, 1959

Posdata, 1959

Ejercicios de castellano, 1960

La hora de la pluma, edited by Victor Ouimette, 1987

Artículos anarquistas, edited by José María Valverde, 1992

Other writings: many novels, short stories, and plays.

Collected works edition: Obras completas, edited by Ángel Cruz Rueda, 9 vols., 1947– 54.

Bibliographies

Fox, E.Inman, Azorín: Guía de la obra completa, Madrid: Castalia, 1992

Sáinz de Bujanda, Fernando, Clausura de un centerario: Guía bibliográfica de Azorín, Madrid: Revista de Occidente, 1974

Further Reading

Fox, E.Inman, Azorín as a Literary Critic, New York: Hispanic Institute, 1962

Glenn, Kathleen M., Azorín, Boston: Twayne, 1981

Granell, Manuel, Estética de Azorín, Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva, 1949

Krause, Anna, Azorín, the Little Philosopher: Inquiry into the Birth of a Literary Personality, Berkeley: University of California Publications in Modern Philosophy, 1948

Pérez de Ayala, Ramón, Ante Azorín, Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva, 1964

Ríopérez y Milá, Santiago, Azorín íntegro: Estudio biográfico, crítico, bibliográfico y antológico, Madrid: Bibilioteca Nueva, 1979

Torre, Guillermo de, Del 98 al barroco, Madrid: Gredos, 1965

Valverde, José María, Azorín, Barcelona: Planeta, 1971

►→ back to ►→ Encyclopedia of THE ESSAY

Please contact the author for suggestions or further informations: architects.co@gmail.com;

►→home

Table of content “united architects essays”

►→*content all sites:

MORE INFORMATION ON MY OTHER SITES:

architecture, literature, essays, philosophy, biographies

Leave a comment