Poetry In Conversation

Kimberly Alidio with Irene Hsu

Teeter

(Nightboat Books, 2023)

I met Kimberly Alidio in the summer of 2021, as a student in their Kundiman workshop, Documentary Poetics: Archive and Counter-Lyric. During our last session, we had been reflecting on Mei-mei Berssenbrugge’s interview in Jacket2, in which she talks about poetry becoming entropic, losing energy, and finding new form. My notes from this conversation include: “You go where the energy is.”

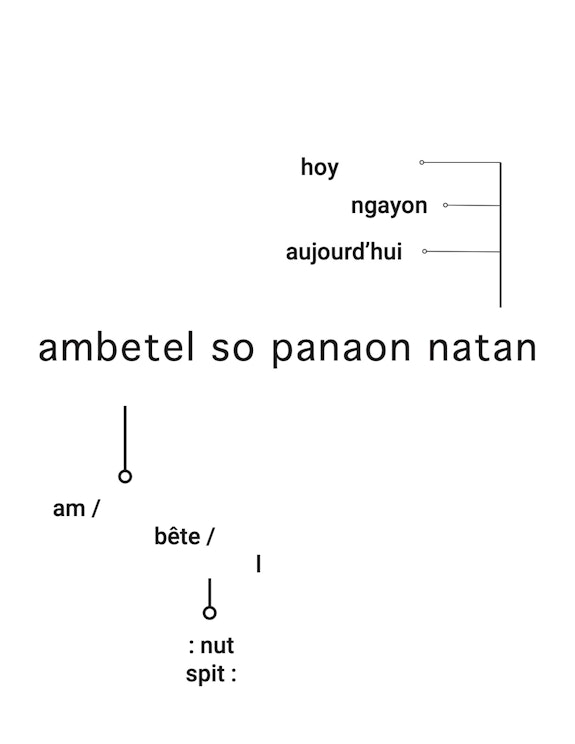

To go to energy, to allow its direction, to follow its guide—this is a driving principle for Alidio’s poetics, which has culminated in their most recent collection, Teeter. Published this past August and awarded the Nightboat Poetry Prize, Teeter itself is a metamorphosis of energy and form. The collection grew out of a 2020 essay, “My Native Language Is Noise,” in which Alidio proposed a practice of being with language decommissioned—that is, withdrawn and autonomous from exchange value. Here is an ars poetica from one poem in Teeter, “To rest in linguistic wombs”:

In my own work, I try to leave some

noise. Of opening toward mutual autonomy from

exchange value. A property relation between speaker &

word softens. Diligence to enter the field of noise &

employing all of the training of one’s ear, to be a co-presence

Overhearing as a way of being simultaneously (30)

On the occasion of Teeter’s publication, Alidio and I talk about the many other shapes that their poetry has taken: documentations of friendship, listening to French New Wave narration, watching YouTube videos of conversational Pangasinan, teaching grammar and sentences in prison, grieving Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, inventorying in order to reckon with life and death. Because the everyday forms the basis for Alidio’s poetry, “all of the training of one’s ear” is nothing short of attuning to the “field of noise” that is living. The below is an abridged version of our conversation, about their poetic practices as a writer, artist, and teacher.

Irene Hsu (Rail): We’ve talked about Teeter as connective tissue. And so I want to ask you about the role of friendships in your writing, and in this period of publication and readings, when the book circulates and connects you to others.

Kimberly Alidio: Teeter is a book of a power vacuum, started in 2019 and finished in early 2021. Three years ago, I proposed speculatively that a “we” might consider being less proprietary about language, whether as a structure, form, medium of identity, or as a territory ruled by the literary writer in the quest for mastery. That proposal is a central axis by which Teeter acts upon me almost autonomously.

I learn that some books manifest their readers; they hail them, waving them over. I am one of Teeter’s readers as well as the person who feels compelled to represent it. As my book’s primary reader, I try again and again to take in what it means to take space in a power vacuum in which language is decommissioned. In 2010, Slavoj Žižek translated Antonio Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks, smuggled out of prison in the 1930s: “The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born: now is the time of monsters.” In our post-institutional imaginations and organizing, I wonder how a poetry reading emerges from this power vacuum. How do we hear together, organized by the forms known as poetry?

Writing into and amidst both loneliness and friendship—this is consistent across my work. Some of it has to do with relationship to language, an attitude or approach, or a need. It occurs to me that there are different forms of loneliness driving particular ways of being a poet. Maybe it’s intersectional identities, too, that have to do with isolation and friendship, companionship and communication.

I’ve been reading a lot around Brandon LaBelle, on the “pedagogy of festivity.” I’ve been writing around the poem as a party, the poem as a field. A container. Ursula K. Le Guin’s carrier bag theory of fiction. I’m thinking about being a teenager and a tween, and that period of transition and intensity, but also total love, where you lose yourself in a group of friends and everything is really loud and chaotic. To survive being an academic in the late 2000s, I took part in Tumblr and blogs. Remembering that brings up noisiness, presence of people coming in and out, instability.

Rail: I have to ask, is there a relationship between the womb and festivity? I’m thinking about how in Teeter, there’s a recurrence of the womb, the oceanic—a container, a version of losing oneself in noise, that requires attentiveness beyond the semantic.

Alidio: It’s working in Julia Kristeva’s idea of the chora as it might relate to the choral and to chaos. What we’re doing is taking motherhood and reproduction and going into the material of that, the sensorial.

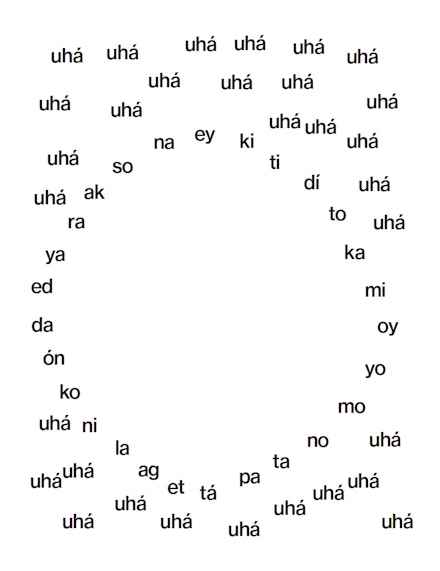

I’m really interested in how we learn language through the practice of repeating, through echoing and echoic memory. In second-generation Filipino American 1980s–1990s Baltimore, people my age would find each other in the basements of our parents’ parties and imitate our parents. These were the only places we could make these sounds—we weren’t going to make them to our parents! Of course, it’s really fraught because you don’t want to see that on stage with a comedian. But I kept hearing these melodies, prosodies, and rhythms in my body, and wanted to make them, too.

It’s an interestingly delayed echo. But if that’s already happening when you’re still inside your mother, the whole container you’re in is reverberating, the container for the vibrations and for voice. It fascinates me that when you cry as an infant, all that comes out. It’s a club. You’re rocking out in there. It’s immersive!

Rail: Then, there are the prose poems in “Histories”—like “Once in a while I live out a story”—where there’s also a relationship to the echo. The poem recreates dialogue in quotes, and there’s this intimate address to a “you,” which makes the whole poem possible, to reject a celebratory narrative of literary stardom. I’m thinking about a lineage of friendship performed through the prose-poem, short essay, fragments, and letters. Is there a form for friendship in your work?

Alidio: Pages 64 through 67 are actually written for a commission by imogen xtian smith, published in Topical Cream last year. It originated from a friend asking a bunch of friends, “How do you continue experimental thinking and art over time?” Maybe because it started off from a friend, it was a question where I could be playful.

The “you” is always very important. It’s a record of a conversation. I was doing these very long sentences in this section to reclaim the form for myself: an extremely long sentence followed by a very short one. It’s true to life in some ways to some of the rhythms of everyday conversation. It’s a style or an utterance, a force of language. How people speak, articulate, and connect.

My prose poems are grounded in and enact relationships, though it’s not just documenting or publishing my diaries—it’s a form, many forms. In life-writing, there can be a lot of anxiety around the boundaries of the self, the “who am I?” But for me, the “you” in the conversation is all that really matters. I’m not really concerned about writing the self. It’s not really about a self, mine or theirs.

So I’m trying to explore that “you.” I have these conversations that are important to me, and I continue having them by crafting language. But also people in my life are hilarious, so why wouldn’t they be in the poem? Literary friendship, artistic friendship, and emotional and personal friendship are really grounding in all of this dark festivity of the literary economy. At the same time, friendships have to shift as people become different versions of themselves across a lifetime.

Rail: Talking about record also reminds me of your Belladonna* chaplet, Room Tone: “When room ambience stops being background, it begins to signify something relative to our sense of survival and precarity, which is perhaps our primal narrative. It is a sign grieving people might look for, or look for a way out of, in the ordinary.” I’m curious about the relationship between grief and the practice of inventorying.

Alidio: I can’t even attempt to describe the different states of grief, and I’ve realized that simply paying attention to art, film, and sound performance creates containers for all matters of change in form. Alvin Lucier’s I Am Sitting in a Room is just, seemingly, a procedural experiment about acoustics and playback. Performers say a script once, record it, play it back, and record all the acoustical dynamics. They keep playing it back until the room acoustics change the speech into tones. It all depends on the conditions of the room you’re in.

Maybe grief allowed me to connect to I Am Sitting in a Room. You can’t write a prompt or a formula, and that’s where the vitality is. Things arrive when you’re ready, when you have the time and the energy to make something. Maybe it’s all about letting go, noting that things are changing whether you like it or not, instead of holding yourself against it and thinking, “This is my self.” Language can change.

Who I grieve and mourn more than ever after Teeter’s been published is Theresa Hak Kyung Cha. She was extremely young when she was murdered. All of a sudden, I feel closer to her, and would’ve really loved to see what her whole career would’ve looked like.

Rail: Can you say more about that relationship? Gray Agpalo has that beautiful passage in Apogee about your “nine muses” represented by nine epigrams in Teeter, including Cha’s.

Alidio: Right, the massive number of epigrams!

I feel like I connect with Cha more at this age; I would’ve really liked to see her being a middle-aged poet so that I can start to understand myself. She worked in whatever medium she wanted because she had things to work out. It’s not like she marketed herself and then studied things and was like, “I’m interdisciplinary.” She just did.

As a young artist, Cha was so brave and open to something that she let in and was able to work with. In some ways, I have a touch of that experience. My books are not things that I understand. I’m not romanticizing myself as a vessel. I do work very, very hard to make them what they are. And helping to make a place in the world for Teeter is a particularly heightened experience.

A lot of Cha’s persona is as a conjurer and a performance artist. People who follow her more directly than I do tap into her through her performances, her moving and still images, her work with Korean shamanism. I respect that, but holding myself apart from my material everyday world is not what I do. Working with my body in space is not my art form. I think of Cha as this person who was practicing, trying things out, giving her work a lot of time and seriousness, and assuming that time, that space, that attention. She wanted people to know what she did, and she didn’t work in obscurity. How do you do what you want, while sharing with the public very deliberately? I still wonder how she anticipated her audience.

Rail: Can you talk more about the relationship between your teaching practice and your writing? As a former student of yours, I see you take very seriously the relationship-building part of teaching.

Alidio: I’m adjunct faculty for a college-in-prison program. I don’t teach poetry but I do teach grammar, which I see as the poetics of form and marking-making in using our alphabetic writing system. In most of my writing life, I write in fragments, outside of syntax. Teaching grammar brings up the politics of grammar, but it also brings me back to the sentence—how it charts space, time, perspective, and narrative. “I’m writing a sentence. This is what the sentence is doing. This is how you build a world.” There’s very much a process of dwelling on relationships between marks and signs, working with the archived possibilities of forms, and seeing what sentences do beyond your intention, so we can collaborate with writing to build worlds.

Last August, right around Teeter‘s publication date, I led an intensive workshop in prison every morning and afternoon. A society built on mass incarceration is not going to be a society great for my book. This sentence came because of having to teach every day, inside, about language while my book was going out in the world. I was feeling the dynamics of it, the exhaustion of it, the labor of it. It's not accidental that I teach about language and writing to incarcerated college students, while I’m helping to bring out a book like this. The activation and the inventorying that comes with using the cultural technique of writing in a conscious, intentional way—that’s where there’s a lot of life and death. There’s a lot of listening to and witnessing writing, what is or isn’t written, all of which can be intense to process somatically.

Rail: How do you hold the grief and rage as a teacher? When you taught workshop to me, so much was about creating the conditions for the work, not just generating poetry. And so I’m just wondering how you work when you’re teaching grammar in a carceral setting.

Alidio: As people might know, it’s kind of ridiculous to go through any workshop, whether it’s a semester, a year, even just a day. What are you supposed to do together, in that extended period of time, unless you really acknowledge one another, and decide to make things together? I could play professor, expert, and have a personality, like quite a lot of professors. But then it’s week three, and what do you really do?

My friend Alexis Almeida has regularly taught McKenzie Wark’s Sensoria’s introductory essay that asks, “What’s the point of scholarship?,” and then discusses it as “our common task.” Scholarship is common. It’s everyday study. I always think of people writing and publishing in these ways, so I can tap into something that’s already happening, something I get to bring in. That helps those of us in a room to think that whatever we do in this room is part of our common task of scholarship. It’s kind of great when we all don’t know what’s going on, because it’s not a failure. It’s part of the process.

Rail: I just want to dwell on uncertainty here—whether in a classroom, teaching, or writing this book. Has unknowing changed throughout the process of working on and publishing Teeter?

Alidio: When I was writing the third section, it was all coming out of me very fast. This is actually the most memorable time, almost like I couldn’t keep up with it. I was allowing myself to think on the page, almost in real time, and generating a kind of intelligence or knowingness I don’t otherwise have but in a field of all the senses.

I was taking things from my journal and notes and paragraphs, and rearranging sentences in reverse order. I really liked that things weren’t inevitable but unfolding in different ways. It was a culmination of work and observations and living. On the Nighboat blog, I talk about voiceover narration in French New Wave movies. The talkiness, the discursiveness, taking time with talking, being unabashedly abstract, conceptual, intellectual, philosophical: that’s what the sentence in Teeter is doing. The sentence is going on and on and on, and it just keeps going!

But when Teeter came out as a book object, I saw how different poems or pieces were actually organized and thematic. That’s when I started having a feeling of uncertainty, an uncanniness. When I talked about this with [my partner] Stacy [Szymaszek], they took the book and picked out pieces in the last section. They read them to me very slowly and commented on them: “This is quite elegant, and beautiful, and this is fun to read. I’m really enjoying this.”

I’m somewhat terrified of this book. There’s a lot of intensity and density. I had been reading super fast in public, with an edge of embarrassment, trying to get through it because there are so many words. But when Stacy read it, and slowed it down, allowed it to be, it became possible to hear. That’s been changing my relationship to the book. Making a place for my book in the world is a heightened thing. I don’t treat it like a commodity so I’m not going to be really calm when I talk about it. I’m not selling it. I’m not selling myself around it.

Rail: The last question is about language having its whole own life. Vi Khi Nao asks you, in a Poetry Project interview: “Did you want your poem to grow a tree? A grapefruit tree? Some earrings that look like jasmine rice?” I love how this question resituates poetry as energetic excess, never fully mummified by the commodity form, even after it enters into the literary economy. What do you dream for the excess, the life force of Teeter to grow into?

Alidio: I have a resistance to metaphor that makes everything pretty. But I love the challenge of this question because it’s hitting on something. As I’ve mentioned, Teeter is a book of a power vacuum. It reflects the post-institutional imagining and organizing of our recent past, if not our present moment. It didn’t occur to me until after its publication this August that the title “teeter” refers to my embodied condition of living through these times, personal and relational.

In the sound writing from the book’s first section, there’s a train. Also a trolley, the one that stopped across my street in Tucson. A train seems so prosaic, while a tree is so beautiful. A train is also kind of fascist. It’s what the Italian Futurists wanted.

I’ll just state it this way: I want things to move. I want people to move together. I want there to be stops, for people to get on and off whenever they want. I want this train to be communal, open to whoever is on it. Something about speed and momentum. And that’s where the teetering is. Will you be thrown off? I’m thinking about the colloquial use of the train to talk about New York City’s subway. Then the Amtrak, Metro-North, and there’s that Hudson Valley connection. People also have their own experiences of the F, or whatever.

Rail: The train is so overstimulating. It’s the most non-metaphor metaphor—I love that.

Alidio: Okay good. Let’s work with that.