Art In Conversation

JENNY SAVILLE with Jason Rosenfeld

“In painting you literally build the realism through the process of the making, with all of that life within it.”

Jenny Saville (b. 1970) recently showed a series of new large pictures of close-up views of monumental heads at Gagosian’s 980 Madison Avenue space. It was a more focused display than her previous exhibition, Ancestors, on West 21st Street in 2018. It also commenced her most trenchant dialogue to date in her work between realism and abstraction. The recent show was titled Elpis—a reference to the personification of hope in Greek mythology. There were 10 paintings, one painted triptych, and one pastel, all dated 2020. She spoke with me via Zoom from her studio in Oxford.

Jason Rosenfeld (Rail): Your Ancestors show felt like something deep, very ambitious, dealing with narrative and history painting and taking on the entire Western male painterly tradition. It really surprised me when I walked into the gallery on Madison and saw just heads and heads and heads and heads [Laughs]. You had traveled to Russia, I understand. And were shooting photographs?

Saville: I was in Moscow, but not specifically to photograph models. I saw a woman on a bridge who had the most incredible face and asked to take her photograph. I hired a photographic studio, and just started photographing people. I built an amazing body of work very quickly and started working on some portraits, which became this group of works. Plus, when I was in Russia, I had the chance to learn about poets, especially Anna Akhmatova, who wrote a poem called “Requiem.” The atmosphere in Moscow was really exciting.

Rail: What was your role in terms of posing the models and framing?

Saville: I set up different situations around this one room. I had my cameras and somebody would come for, say, four hours, and I just worked. I had a head on a mirror and a head looking into daylight. Because it was a photographic studio there was a variety of colored backdrops and I tried working with a bright red background which I would never usually use.

Rail: Like in Elpis, the triptych in the show.

Saville: Exactly. I would never usually have done that because it's so hard to use brightly colored backgrounds, because they just say “Francis Bacon.”

Rail: As in Bacon's Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion from 1944.

Saville: Bacon plowed out the most remarkable space for himself with high-colored backgrounds. I've always steered quite clear of that and used more neutral backgrounds. But in Moscow I used different colored backdrops because they were there in the photographic workshop. I love the effect it had on the coloration of the flesh. I started being able to use green and it just created this amazing flesh reflection with the red background that I hadn't seen before. I went for it and I thought, “Okay, I'll try and do it without being too caught up with Bacon.” The way that Matisse would put green next to red, like I used in Rupture, that green neck with a red background. Matisse did that all the time. And actually, I probably looked at Twombly more than Bacon, when I was making Elpis and Rupture.

Rail: I took photos of all the eyes in the works. There were some where you see the shadowy figure [Chasah], or the studio windows [Second Nature]. Like in a Parmigianino or Baroque painting and it was exquisite.

Saville: When I am working I want to use the maximum capacity I've got as a human being. I always paint eyeballs first thing in the morning, because I have an incredible level of focus at that time. I'm very risk-taking in the evening, when I get more tired and I don't care as much—I'm much more likely to take big risks. It's a different substance, the jellied nature of an eye, what it is and what goes through it. One model had these enormous eyes. I could look at her all day long, I was so mesmerized by her. She was a student at the University in Moscow. She had always been told since she was very young that her eyes were too big. She had this nervousness to herself, but at the same time an ability or an extra something through her eyes. I've always been attracted to that kind of model. I've painted blind girls or people who have a sense of being looked at, or being nervous about being looked at. They have a kind of solitude, a sense of tragedy, that I find very appealing.

Rail: Big eyes are a virtue now—like Anya Taylor-Joy who plays the lead character in The Queen's Gambit.

Saville: Exactly! It's really funny, because a collector of mine sent me a picture of her and said, “I bet you'd like to paint this woman.” And I'd never heard of that TV show. I like that tipping point where conventional beauty becomes slightly questionable, where extreme beauty is tested. That’s a very interesting border. I've always been aesthetically drawn to people like that, where there's a tragedy, where there's a look that's powerful but vulnerable at the same time, people who have had a birthmark so they have a worldliness because they've always been stared at. They got used to managing that position they're in, and even though they're vulnerable, they have an inner power. There's a kind of inner strength to the tragedy.

Rail: It makes them more compelling. Are these works the product of projections or do you make them free-hand?

Saville: I print very big photographs, almost one-to-one scale. I don't paint the whole thing at once. I paint in sections, and then I build them up from there. The photographs give me a structural and tonal scaffolding.

Rail: Are you working on multiple canvases at once?

Saville: Usually I have several. At the moment, I've probably got 20-something canvases on the go, but I’ll rarely finish them all. By simplifying the heads, and only working on heads, I was able to push my painting.

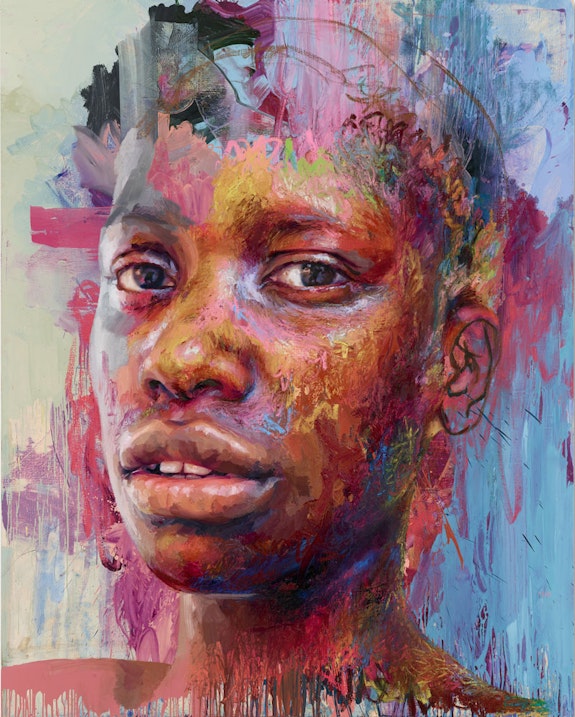

Rail: The colors that you're using now, as in Chasah, they feel like such a vivid departure from previous things that you were doing in your works.

Saville: The year before lockdown I traveled a lot. I saw a lot of art in person, and a lot of Monet. In reproduction Monet doesn't do as much as when you see it in the flesh. It's just astonishing. The simplicity of his motif allowed him to extend what he was doing in paint with color and surface. This became interesting to me as a way to develop my own work. Ancestors was so complicated. I had influences from all across art history. And it was like spinning so many plates. I had pietàs, I had Orthodox icons from Russia and Greece. By just having heads I was able to concentrate. It was liberating to have something so solid, and working off that became exciting. I've also used a lot of oil bars, and they come in this amazing range of bright tones and hues. So I've got this big range of sticks in front of me, like big lipsticks. They're creamy and you can move them in and out of tonal paint and build them up like tapestries.

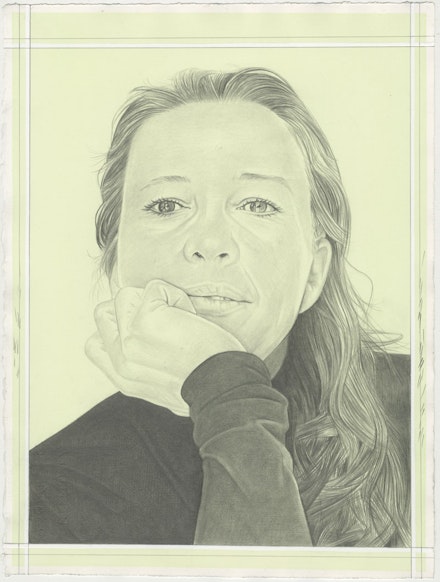

Rail: What is your process with the pastels?

Saville: A pastel such as Prism is built up using lots and lots of images. And if you draw into an image that already exists, it's almost like you cut through it. You see the multiple eyes and it's like you can go straight inside the image. I found that a very powerful way to work. There are probably about 30 heads in Prism. I draw them and slowly build up images of the model from charcoal. It was black with a bit of red at the beginning. I did a drawing before called Electra on raw canvas with charcoal and red pastel. I knew that I liked working on that surface and I size the raw canvas so it's got a kind of grip to it and a slight sheen from the rabbit skin size. That surface works. Mostly I've used pastel on raw linen. Often when I make developments, they rise up because of mistakes. Prism is on a canvas my framer sent that only had a thin layer of rabbit skin glue, which wasn’t sufficient to paint on. So I tried out pastels on it. Because you're so free with it, because it's a trial, it often works so well. I bought this set of vivid pastels based on Monet's garden. We were heading towards springtime in Oxford, I was walking in the garden a lot and looking at flowers and the colors and trying to get this color intensity and trying out different things, like using that red on the neck, for example. It was just exciting to be able to make something so electric. Using the rawness of the canvas makes that stand out even more.

Rail: It has a neon quality, especially the linear elements.

Saville: Exactly. And how far can I push that? It was very organic. I worked for a few hours every day with a very relaxed attitude. Once I started using more electric colors it became rapid. I made different marks than ones I've made before. I used to always paint in flats. That's the way I was trained to paint, through Cézanne’s thinking about constructing form. Now dripping has become a big tool for me, from looking at Twombly and late Picasso. I've tried to think about the poetic possibilities of paint, how you can use it from raw canvas all the way up in terms of staining, dripping, putting it on the floor, drawing through wet paint, wet into wet, dry, dragged over the top, oil bars in wet, up to impasto. Because I was simplifying the subject and structure with the heads, I was able to explore that much more than I've ever been able to. It's been one of the most exciting bodies of work I've made.

Rail: But in a picture like Requiem (Akhmatova), there is a range of applications, drips that then puddle on the floor, the way the face has been kind of attacked in the center, and then up and around the right side of her face. And a contrast to the resolved eyes and then the lips and the nostrils.

Saville: Abstract painting has been one of the biggest influences on my work. I love de Kooning, Twombly. Looking at abstract painting has probably informed my painting more than looking at figurative painting. For years and years I've been looking at it and not really known how to get it into the work. I've also collected images of graffiti from all over the world and I often ask myself, “Why are you spending hours and hours collecting this stuff? When is it going to arrive in the work?” In these paintings it is starting to surface. That's what became exciting. Trying the drips and working over the top then drawing through it. I never let myself say, “Well, you can't put that with that. You can't have a realist nose sitting with very abstract paint that I've done on the floor,” for example. I told myself, “Just work in the moment and make it work.” I read a quote from the Russian poet Marina Tsvetaeva to do with embracing the impossible. I tried to make something that embodies form and formlessness simultaneously. If you take something like the painting Second Nature, even Cascade, there is a breaking down and building up of form at the same time. That's very difficult to do in paint, to make it have absolute, solid form in a recognized way and complete abstraction. It’s a ridiculous aim, really, but the work is a document of that endeavor.

Rail: Were the “Fates” in the Ancestors show transitional, then?

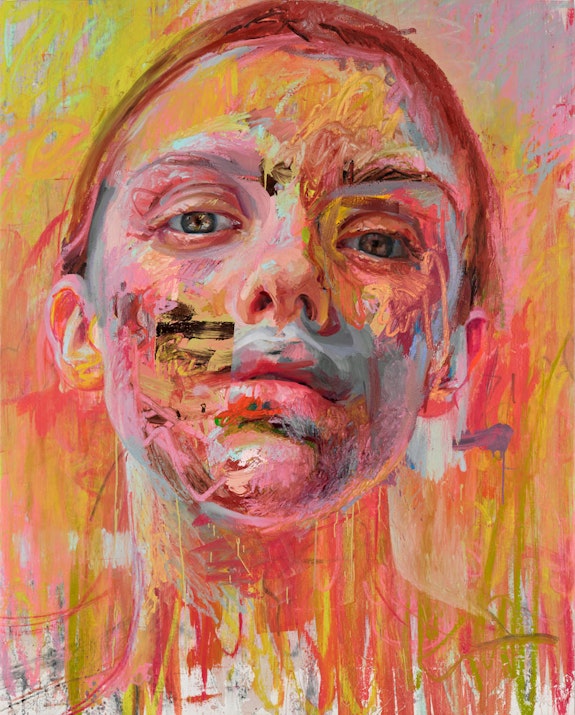

Saville: Yes. And Elpis will be transitional to something else. I yearn to find a language which harnesses what it's like to live in the 21st century. It's about reality and pictorial space, because as a painter, there are only so many elements that you've got, and I like those limitations. When I was younger, I found that painting couldn't transform itself, that it was this very specific language. Now I find that to be very much its strength. What is pictorial space? How does that have an effect on you? How to build that space in a painting? From looking at Egyptian art, which uses psychological space with changing scales of bodies within a pictorial system, to the way de Kooning makes a shallow form of painterly space. How can you use all these different spaces? How can you harness this history of mark making up to when you see heads on a computer? At the moment I'm intrigued by FaceTime. When you get a little FaceTime head on the phone, it's a secondary head. In Russian icon paintings you'll see a big body, and then you'll see these little tiny images within the big body, like a circle in the center of the chest, for example, exactly like on an iPhone. I think about that kind of relationship of pictorial space all the time. A work such as Cascade is really just following my instincts. I would normally have made more of a form out of it, I would have painted the teeth, I would have painted the chin, but I let it be much looser. And the eyes just held the whole thing together. This was walking further out on a tightrope than I’d done previously.

Rail: Virtual and Cascade are definitely the most daring.

Saville: Virtual was an attempt to try to paint out what was happening during the pandemic. I was talking to everyone on Zoom. I was watching CNN news readers with shadows behind their floating heads. Suddenly, our pictorial language became very intense.

Rail: Because they weren't in the studio, because they were all in their own houses or rooms?

Saville: Exactly.

Rail: And so it wasn't controlled.

Saville: There was a strange intimacy, but at the same time a dislocation. We were all experiencing exactly the same virus, the same fears. We were forced to communicate only virtually. Suddenly, I just felt that I knew how to depict that. Or at least I wanted to try. Virtual was the result. I'm always fascinated by computer programs, the way that they create depth in computer images on a screen. They try to replicate the real world, they put shadows behind images. Virtual started as a series of collages from cut up photographs and drawings of my upside-down head when I was in the bath. It was a selfie that I then cut up. I started re-photographing the collages to create shadows within the picture. I tried all these different ways of building space.

Rail: It seems freeing because it's allowing you to experiment with perspective, dimension, even something like continuous narrative from the Renaissance, multiple images doing different work simultaneously in the same frame.

Saville: The lockdown intensified life and made me braver. It's not necessarily a departure because I've painted large-scale heads before, but I'd never played with the language of abstraction so explicitly.

Rail: And it's very different from how other artists typically work directionally in the sense that you don’t work from the resolved form and then abstract it. That's how Cecily Brown often works. Even thinking about Jacques-Louis David, when he made a painting, he would paint the entire figure in the nude first, and then paint the clothes on top, and then the environment, working from the resolved body into something either more finished or more abstract. But you're working first with an abstract surface, and then teasing out imagery or building visible imagery.

Saville: It depends. I try not to have a system. Establishing a figurative structure first is a good armature to build on. But it’s not the only way to do it and I’ve tried to seek out ways that might bring greater realism. Once I start realizing I've got a system I try to work against that. I don't want to have a way I do this, because every time I do that, not only do you get bored, but you become mannered, and I fight against being too mannered. I'm figurative, which is, you could argue, an easy way to become mannerist, but I always want to test out what I am doing. So I try to start in different ways. Like using different colored grounds, or starting very abstractly on the floor. What's good about starting on the floor with an abstract approach is that it gives an immediate nature to the work, it's like laying down a problem. Then, if you try to build out a nose from that, for example, it sets up interesting contradictions in the paint. Suddenly you've got a kind of powerful argument going on within the painting.

Rail: What do you mean by “nature,” because I've heard you use that before. Does that mean that you give a kind of base for how it's going to develop from there?

Saville: Yes. At the moment I've got three or four paintings on the floor in my studio, which I started off using 20 different colors in bowls—from blue, bright red, alizarin crimson, sap green. Something transparent that has a punchy nature to it. Then if you add a pale paint that's lighter over the top, and you run it in wet, you get multiple tones and movement. And I've noticed that if I start the other way, more structural, you tend not to be brave enough to just go for abstraction on the top, because you're already in the journey of making something and your instinct doesn't want you to destroy it. So I start working from an abstract base, and then build from there to force my hand. And by doing that you can sort of draw an ear through very abstract paint and you make something that you would never arrive at, if you had to rationalize that. I would say there's a kind of arbitrary nature to it, which relates to how nature is. So that became kind of exciting, in the same way that you look at a corner of a de Kooning painting where one color has gone through another, and it's so evocative—you don't know what of, but it feels so good. I definitely try to exploit how far you can go off realism. Because you get to another level of realism, which is much more exciting than regular realism. It's almost like the way van Gogh intensified it in his paintings. I like to push the realism as far as I can. I definitely don't want to be abstract, I see myself as a figurative painter, but you access a heightened level of realism by breaking it all down and then building it back up. So the whole process of my work is a route to greater realism. It's using the nature of paint and then rebuilding the form of the head and then maybe breaking that down again, and rebuilding again. It's almost the way life works or a relationship works where you have an argument and then you're back on. You've reconciled something, then you have another argument, you reconcile it and that's the way life builds. In painting you literally build the realism through the process of the making, with all of that life within it.

Rail: Do you start off with it on the ground, and then move to the wall?

Saville: Volta was started on rolled-out, pre-primed canvas that was not on a stretcher. I started it on the floor with a liquid, lead, oil-based primer with oil bars, and I draw with the oil bars and then pull the primer over the top, and it kind of embeds the lines within the primer, so that the lines themselves almost go back in history, because it's the same way that I use charcoal marks and then rub them out because they get embedded in the canvas. And then I use oil bars over the top and the bottom part of the canvas with those kind of abstract bits. They are as fundamental to the painting as the eyes. And that's from almost having a kind of abstract painter’s eye. It feels like a curtain or a way to see through the painting. I like to play with the artifice of painting. I think I got that from Giacometti's heads, where the bottom part of the painting is so beautiful. It was from looking at those works that I became conscious of all aspects of the painting. It's not about the personality of the portrait sitter.

Rail: And the likeness, of course, right?

Saville: I'm trying to access something universal, which is what abstract painters were trying to do. When I've worked with models that I don't know, or faces from medical books, that's been exciting to me. Because the journey of getting to know the landscape of their head is through the process of the making, and that there's an intimacy in that. I started to work from photographs, and then to break down my working process into small elements. Like the way a musician composes. Mixing colors separately to concentrate on individual tones, looking at photographs in pixilation, using various sources of imagery, not just photographs of models. It was a dissection of my painting process. And that became a much more exciting way to make a painting than working just directly from life. The way that I work is much closer to life than it would be if I had that person in my studio.

Rail: The musician analogy is really potent. I think of musicians like Paul McCartney or Lenny Kravitz, who play all their own instruments on some of their songs, so they record track after track after track and then have to put it together and you're kind of composing in the same way.

Saville: Yes, it's exactly like that. This show's got so many different methods of putting paint on a canvas, from a stain to a drip. The range of mark-making tools that I've used as instruments have a poetic sense, like word couplings for a poet. When your eye scans the marks in the bottom of Volta, it emanates something poetic. I try to build off that. This painting doesn't have a background. It was a limited amount of space that I could get if I wanted to use bright yellow and bright pink in the negative space around the head. And so there's a limit to the amount of space that could go around that neck. I try to hold that in the balance. How much do I need, without having to use a traditional way of making space behind that neck? How much can I get away with in terms of keeping the abstract nature of the bottom marks while still giving you a sense of the form of the neck? And I work like that all the time now.

Rail: The necks often don't line up, they're very narrow, very thin, they're a little bit to the side. It's like those floating heads in Elizabethan paintings where they're kind of hovering on lace collars.

Saville: Nothing's ever completely fixed, but the heads still have a sense of three dimensionality in the sculptural sense. That's why things like ears become incredibly important to me, because you can literally fix a form, whether it's an eye structure, the side of a nose, the dip below the lip, or especially ears, because ears are so human. They've got a landscape within themselves.

Rail: Bernard Berenson said that ears are the way that you can distinguish painters. That's the root of connoisseurship for him. He talks about the nostrils and the ears as the way that you can tell which artists did which painting.

Saville: I love the turn of ears. They've got an architectural system all of their own. There’s soft flesh at the lobe, cartilage structure as it turns and red reflected heat at the outside edge. Even the most conventionally beautiful face can have odd looking ears, so they give you extra human value. I use them like a hook in a painting.

Rail: I was thinking about the concentration on the face, the open eyes, the open mouths. It reminds me of Bernini’s idea of a “speaking likeness”—it breathes, it has its kind of organic energy, but also just knowing myself as a father, and the person who has taken all the photographs of my kids for 18 years. I have probably 30,000 photographs. When you're a parent you're always looking at your kids, at their faces. They're hardly ever looking at you in the way that you look at them. And that kind of intensity of vision is something that comes out in these pictures, because we could talk about beauty, we could talk about desire, but there's a kind of fixity of vision in these, which I agree with you lends them a new kind of realism.

Saville: I don't know how you feel about having children. But I found there's a level of love that I didn't actually know that I was capable of.

Rail: It's ridiculous. I agree.

Saville: I look with just deep admiration at the way my children are looking at a tree, for example, or they see something and you just know that they've got this amazing beauty and your connection to them is so strong. And you're right, you can take photographs of them, and they don't even know they're being photographed, they just don't care if you've taken the millionth picture. So you get this very free vision. Maybe I’ve carried that on with models. It's been a huge influence on me, being near my children growing up and watching them and their creative freedoms, not just in terms of when you watch them making marks themselves as babies, but their social freedoms.

Rail: What's it been like in lockdown? In a way, it's never been a better time to see art on your own in a focused way. But it is a very strange sensation to be going around to art galleries and museums and they're basically depopulated.

Saville: I haven't left Oxford. I've just been making this body of work. I have experienced such an intensity of feeling in these portraits. Maybe the marks and energy and color were a sort of resistance to the virus and life’s restrictions. As if this situation can't stop me making art. I felt really empowered through it to make something so simple as a head and use as many colors and mark-making abilities that I could muster in myself, in the universe of my studio.

Rail: You're taking something so elementary, and turning it into a new discourse in your work.

Saville: I go to Greece quite often, to the archaeological museum in Athens, and look at sculptural heads, endless heads on plinths. When I look through my iPhoto there are hundreds and hundreds of heads from museums around the world, from China, Greece, the Met. I photograph head after head from low to high viewpoints. And that's exactly what I did when making the heads in Elpis using a viewpoint that I've had in my work all the way through. It's an instinctive way of making something feel epic.

Rail: The worm's eye view. Like the sculptors in Greece, on the Parthenon, everything was elevated and you're looking up at it from below.

Saville: Yes. It creates a sculptural feel.

Rail: Let's talk about sculpture a little bit, about Michelangelo. I was intrigued to hear about your project in Florence.

Saville: The curator Sergio Risaliti knew I liked Michelangelo, and invited me to Florence. I didn't just want to see the sculptures. I asked him to walk me around, I wanted to know where Michelangelo walked, where he ate, all the nuts and bolts about his life. I spent time with the scholars at the Casa Buonarroti. I couldn't believe the drawings. They kept bringing one out after the other and they were breathtaking. That’s where our conversations started about doing an exhibition in various sites around the city. I visited his various sculptures in Florence and am making a work around Michelangelo’s Pietà at the Opera del Duomo Museum.

Rail: The Pietà from the Opera is such an extraordinarily compact thing with the four figures and the self-portrait at the top as Nicodemus.

Saville: It's astonishing in the flesh, it's just unbelievably powerful. The technique Michelangelo has of having the rough marble and the polished marble has been the basis of the Elpis show, that idea of showing that the marble is nature. And what you do to transfer it into a body is exactly the model that I use for this show in the abstract areas of paint and then you build it up into a nose for example. All of that comes from looking at Michelangelo, the way he built the flesh from the rock. I use that as a kind of technique model to put into my painting. It’s Michelangelo's sublime humanity, to be honest. Because he has a universal feel. And he creates something that couldn't exist in basic life, but it's so real, and so he's been such a guide to me. The Pietà composition, for example, there's no way that could ever exist in real life. The tectonics of the sculpture, the way he manipulates reality, turns you back onto life more forcefully.

Rail: In terms of its engineering, in terms of its balance and weight.

Saville: Those bodies couldn’t exist exactly in that way, and yet you absolutely believe its human mass, it’s heightened and concentrated reality.

Rail: But the unfinished elements are the things that make him human, right? I mean, the fact that Michelangelo attacked this work when he was 80 because it wasn't right for him. That commitment is partly why we continue to study him.

Saville: He was solitary. When I read about him I feel it's okay to be like this, it's okay to be a bit secretive, and look at what he made, look at the testament of what he created. It stops you worrying about doing an interview, or going to an opening, or being at a party or whatever, if you only want to be in the studio and that's actually what you want. That's all he did. And you think if you want to get anywhere near this level of understanding of the medium you're working in, the immersion has got to be absolute. I go to bed with his books in front of me or his letters. My life has got to be dedicated to my work. He's guided me in that endeavor. The drawings I'm making are going next to Michelangelo! It's certainly a way of making you try harder. If you feel tired on a Tuesday night, and you can't keep working, you just keep bloody working. You simply must find the energy. If I think about this exhibition too much I get paralyzed, but I try to use it as energy to be the best I can, to try to push as hard as I can. As long as I keep it on the positive side, I think it's fine. [Laughs]