The future of war is networked, regardless of platform.

WASHINGTON: According to Pentagon planners, networked capabilities — like Joint All Domain Command and Control (JADC2), the Army’s Project Convergence, the Air Force’s Advanced Battle Management System (ABMS) — effort and more are among the keys to the new American way of war, All Domain Operations. All of them depend on software and networks — and many of them don’t communicate well with each other.

It seems like a problem that should be solvable. But Heather Penney, the famed F-16 pilot ordered to ram Flight 93 on 9/11, is concerned that the department’s “bean counters” and “lawyers” who often stifle innovation and slow the development of critical and complex software might make All Domain Operations unachievable.

“If used to their full potential, advanced networks, technologies, and algorithms can provide key operational advantages such as rapid adaptation, as well as enable complex multi- domain kill webs and decision optionality. These attributes are necessary to disrupt adversary strategies to defeat U.S. and allied operations,” says a new study by Penney and Dave Deptula, dean of the institute and a member of the Breaking Defense Board of Contributors.

Credit: Mitchell Institute

Penney, who now works with the Mitchell Institute, identified Pentagon budget builders and acquisition lawyers as key obstacles to moving complex software systems from research and development to the battlefield.

“Believe it or not, we found that the primary barriers to being able to field the software tools are bureaucratic. The first barrier is simply the color of money. Money scares people because you can go to jail if you get it wrong. I mean, it’s serious stuff,” she said Tuesday.

“But the funding categories are fundamentally ill suited for the pace of software development, the rate at which we obligate money for different activities and the limitations we have on who can spend what for what prevents us from fielding software tools. So funding categories are a huge barrier.”

This matters because, as she put it, “our battle networks, our data links are becoming the foundation of how we fight. This reliance will only increase in the future. These architectures will need to be able to fight, even while adversaries are attacking our networks. To prevail in a peer conflict we will need to be able to adapt our architectures faster than they can attack.”

China recognized this years ago and plans to fight what it calls an “informatization’” war, targeting America’s information networks and operational architectures instead of engaging in a head-to-head clash of kinetic systems.

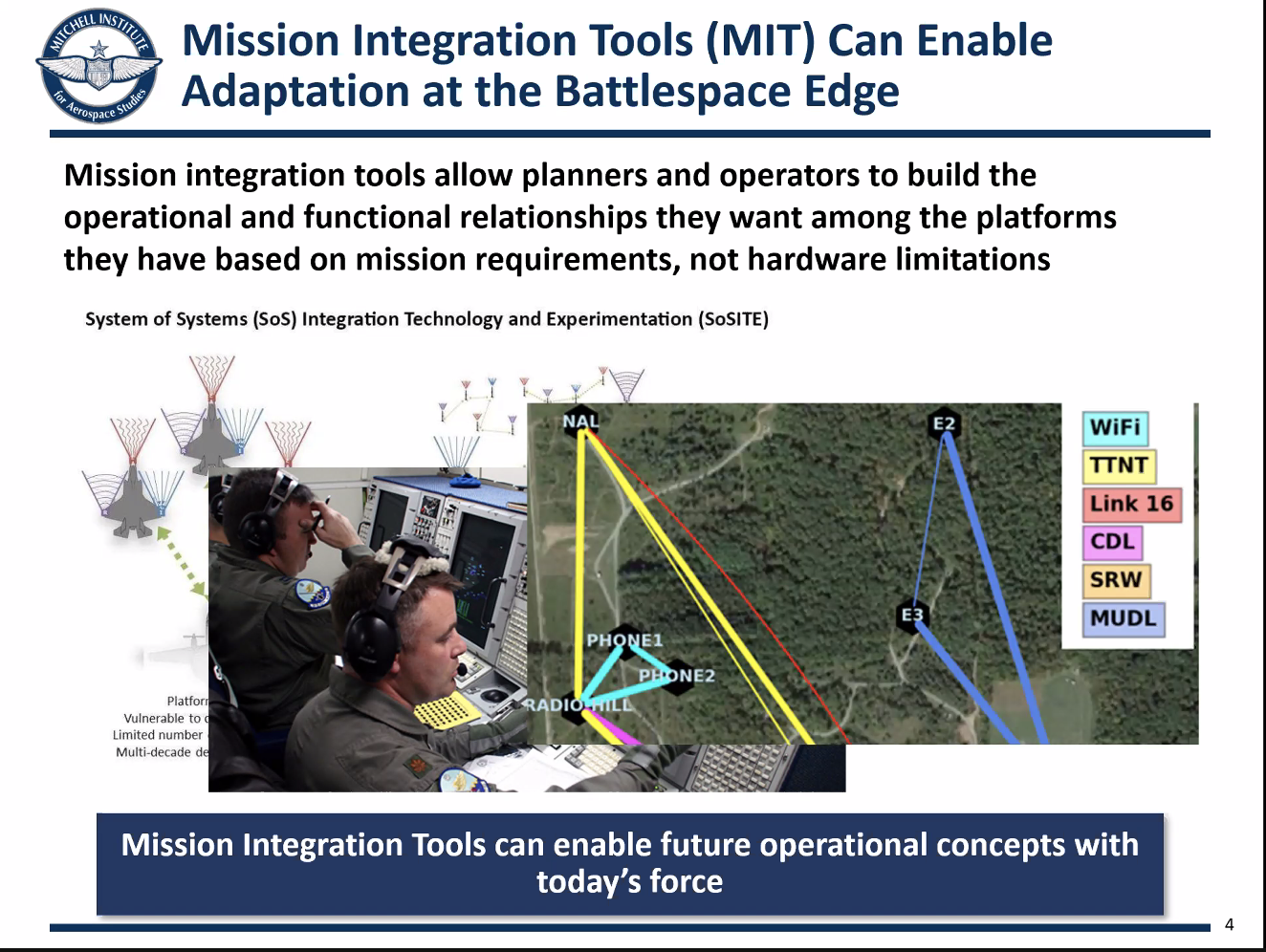

Credit: Mitchell Institute

So tying together America’s disparate networks with tools that can adapt is crucial, the study finds. New software programs, which Penney and Deptula, call “Mission Integration Tools” may be key to this.

Two of them are very promising, Penney said Tuesday. DARPA’s Adapting Cross-Domain Kill Webs (ACK) and its System-of-Systems Technology Integration Tool Chain for Heterogeneous Electronic Systems (STITCHES).

“ACK,” the study says, “is a decision aide that creates and analyzes thousands of potential kill chains” using a variety of platforms, systems, and weapons. It actually weighs the “value” or “cost” of switching targets. ACK is a DARPA invention.

STITCHES helps move data “across different systems without changing message formatting or losing data,” the study says. It doesn’t “require a universal standard. Instead, it uses a library of prior translations and a technician-usable software tool to auto-generate software patches. These patches enable data exchange between existing systems and functions that use different languages and coding. It is software that writes translation software.”

This means that the Air Force or other services don’t need a common standard. STITCHES ties everything together (as it were). Indeed, DAPRA demonstrated STITCHES relevance during Air Force’s ABMS experiment last August.

Understanding how all these networks, Mission Integration Tools, communications and weapon systems work together requires highly specialized knowledge. The Air Force’s solution is a new role, called Joint Interface Control Officers (JICO). Penney and Deptula describe JICOs as “operational and technical experts who go through a year of extensive training to ‘manipulate complex link architectures in order to maximize the combat effectiveness of joint and combined forces in dynamic operations.'”

For year, the Air Force has been grappling with how to develop and maintain a core of officers who will understand the complexities of Multi-Domain Command and Control (MDC2) ever since then-Brig. Gen. Salty Saltzman began to hammer out the way forward on what we now know as All Domain Operations.

Building, using and understanding a system this advanced will probably force the Air Force to create a specialty so that promising officers and enlisted can remain with MDC2 for much of their career, Saltzman believed two years ago: “We need to formalize and professionally develop a cadre for operational C2.”

For anyone who doubts getting involved with ADO, JADC2 and related issues at the Pentagon will be good for their career, Lt. Gen. Saltzman is now deputy chief of space operations for operations, cyber, and nuclear for the Space Force.