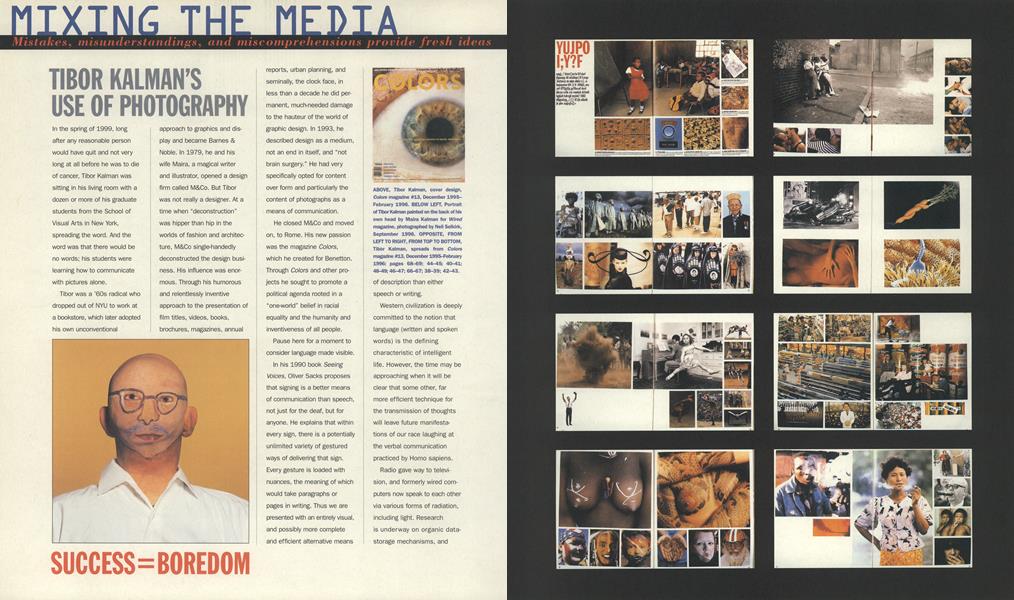

TIBOR KALMAN’S USE OF PHOTOGRAPHY

MIXING THE MEDIA

Mistakes, misunderstandings, and miscomprehensions provide fresh ideas

In the spring of 1999, long after any reasonable person would have quit and not very long at all before he was to die of cancer, Tibor Kalman was sitting in his living room with a dozen or more of his graduate students from the School of Visual Arts in New York, spreading the word. And the word was that there would be no words; his students were learning how to communicate with pictures alone.

Tibor was a ’60s radical who dropped out of NYU to work at a bookstore, which later adopted his own unconventional

approach to graphics and display and became Barnes & Noble. In 1979, he and his wife Maira, a magical writer and illustrator, opened a design firm called M&Co. But Tibor was not really a designer. At a time when “deconstruction” was hipper than hip in the worlds of fashion and architecture, M&Co single-handedly deconstructed the design business. His influence was enormous. Through his humorous and relentlessly inventive approach to the presentation of film titles, videos, books, brochures, magazines, annual reports, urban planning, and seminally, the clock face, in less than a decade he did permanent, much-needed damage to the hauteur of the world of graphic design. In 1993, he described design as a medium, not an end in itself, and “not brain surgery.” He had very specifically opted for content over form and particularly the content of photographs as a means of communication.

SUCCESS=BOREDOM

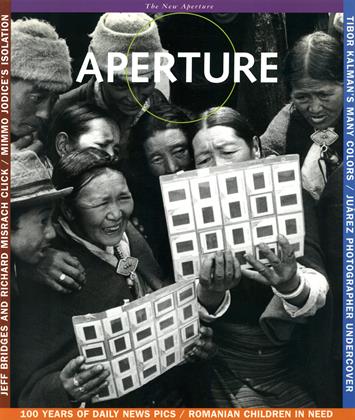

He closed M&Co and moved on, to Rome. His new passion was the magazine Colors, which he created for Benetton. Through Colors and other projects he sought to promote a political agenda rooted in a “one-world” belief in racial equality and the humanity and inventiveness of all people.

Pause here for a moment to consider language made visible.

In his 1990 book Seeing Voices, Oliver Sacks proposes that signing is a better means of communication than speech, not just for the deaf, but for anyone. He explains that within every sign, there is a potentially unlimited variety of gestured ways of delivering that sign. Every gesture is loaded with nuances, the meaning of which would take paragraphs or pages in writing. Thus we are presented with an entirely visual, and possibly more complete and efficient alternative means of description than either speech or writing.

Western civilization is deeply committed to the notion that language (written and spoken words) is the defining characteristic of intelligent life. However, the time may be approaching when it will be clear that some other, far more efficient technique for the transmission of thoughts will leave future manifestations of our race laughing at the verbal communication practiced by Homo sapiens.

Radio gave way to television, and formerly wired computers now speak to each other via various forms of radiation, including light. Research is underway on organic datastorage mechanisms, and while brain implants may still be some way off, if and when they happen, it seems unlikely that they will be communicating with one another via loudspeakers. The forms and mechanisms for the communication of ideas and information will be very much up for grabs when all this stuff starts to coalesce.

New ideas exist in high art (often called art) and low art (sometimes called vernacular).

Back in the real world, the genre of using “found” stock photographs for telling a story, almost to the exclusion of text, has been around for a while. Buckminster Fuller’s / Seem to Be a Verb comes to mind, and several chapters of John Berger’s Ways of Seeing. Both of these visionary authors turned to “found” images after deciding that mere text was inadequate to the task of communicating the scope of what they were proposing. Tibor also reached the point of trying to use “found” stock photographs as language, literally. The last issue of Colors (February 1996) that Tibor edited cautioned the reader on its cover: “Warning: this magazine contains no words. Start here.” The solophotophobic reader had little cause for concern, however, for in fact there were many words within. An editorial of 442 words excuses the reader from continuing to read after 83 words, on condition that he or she spend three minutes looking at any one photograph in the issue: an unabashed plea for the reader to try “reading” a photograph.

Tibor explains himself thus in the issue’s editorial: “It’s not that we’re against words. We just think people expect too much from them. They expect words to tell them what’s going on in a photo, when all that words really do is impose an interpretation. . . . Words literally tell us what to see . . . The only way for you to understand is by looking. You interpret visual signs—gestures—that if guided by text, you might never have noticed.” The point is that as with sign language, in a given period of time, the sheer volume of information conveyed visually by a photograph can far exceed any verbal or written description of the same sub-

“THE ONLY WAY ANYTHING HAPPENS IN THE WORLD IS BECAUSE OF EXTREME CHARACTERS. THE CULTURAL LIGHTS OF THIS CENTURY ARE ALL MANIACS”

ject. Further, and critically, descriptive copy actually creates a myopia that reduces the viewer’s access to the truths in a picture. Flowever, Tibor does admit that between the photographer and the editor there is at least as much opportunity to manipulate the viewer as there would be if the subject had been verbally described.

For the 1987 Limited Annual Report, Tibor was mandated to reassure shareholders that, despite the disastrous drop in nificance of all that information is will be different to each viewer. When photographs take on the role of narrative vehicles, part of the function of each succeeding image is to try to correct any divergence from the intended reading of its predecessor, before it can get on with furthering the story.

the company’s stock value following the stock-market crash, the company’s top management was the toughest in the business and would prevail. I was dispatched by Tibor to Columbus, with instructions to make the presidents of each division “look like sons of bitches.” They were, and I did, and the results worked admirably well in all areas except repeat business.

While there may be masses of fascinating information in each picture, just what the sig-

I have never found much in between-Tibor Kalman

Despite this, in Chairman, his 1997 six-hundred-page biography of Swiss furniture manufacturer Ralph Fehlbaum, Tibor manages to generate a very strong and convincing feel for his subject with just 225 words distributed over twenty-nine “title” pages, very much in the manner of a silent movie. The first hundred-odd pages of the book are a mildly amusing collection of pictures that introduce the reader to the idea that chairs evolved along with mankind. And there is something else going on simultaneously: we are being introduced to the language, or perhaps the code, in which the book is written. This language/code is a mental photo-cubism. We are shown many perspectives of the worlds that interest Fehlbaum, and in the process form a vivid picture of the man himself. At the same time, through the book’s references to many artists, architects, and designers, we get a feel for the larger world Fehlbaum inhabits. Interestingly, a number of the photographs in Chairman also appear in the “wordless” issue of Colors, suggesting perhaps that there is actually a vocabulary or alphabet emerging, or that there is a finite number of amusing, detailed, and informative images available—or perhaps that Tibor had some images he just couldn’t resist.

What is it that makes an image irresistible?

If a photograph does not strike one immediately, does not draw one to it to further scrutinize and delight in its details, it is probably without merit. I can’t think of a photograph that I love that didn’t haul me to it, like the irresistible tug of a child dragging his parent down the beach to inspect the carcass of a large rotting fish. There is so very much to look at, a total visceral overload. Warning: No fish, no tug.

Understanding this is the key to successful story-telIing-without-words. For it to work, the sequence of initial responses must provide the crude outline of the story, containing the blunt philosophical thrust, tugging the reader along.

Photographs as illustrations in published work, with rare exceptions (such as when the picture becomes the event, as in the photograph of Jack Ruby shooting Lee Harvey Oswald), serve primarily to draw attention to and sometimes guide copy. Using pictures that do not transcend their subject matter, in lieu of copy, is not materially different from using a few simple words. Using interesting pictures without text, however, is certain to lead people in directions of their own choosing. For Tibor’s 1998 42nd Street construction-fence project, the objective was to give back the street to its denizens. Passers-by were invited to be photographed then and there, on the sidewalk, momentarily plucked from whatever they were doing. The assumption was that the sheer variety and vitality of the subjects, when presented as hundreds of posters along the street, would reflect and re-invigorate the street while there were no businesses there to do so. More than a thousand people were photographed, at the rate of one per minute over two days. Superficially their vitality is infectious; on closer inspection, many of the pictures continue to fascinate.

Last year, as he guided his final group of School of Visual Arts students through this anarchic medium, Tibor was (again) inviting chaos. But he hoped that by entrusting them with the richest, rawest material possible, they would draw their own conclusions, and both the students and the conclusions would be his.

Neil Selkirk

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

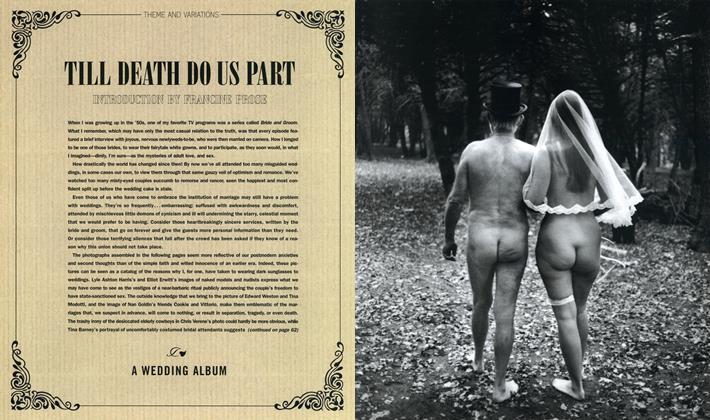

Theme And Variations

Theme And VariationsTill Death Do Us Part

Spring 2000 By Francine Prose -

Profile

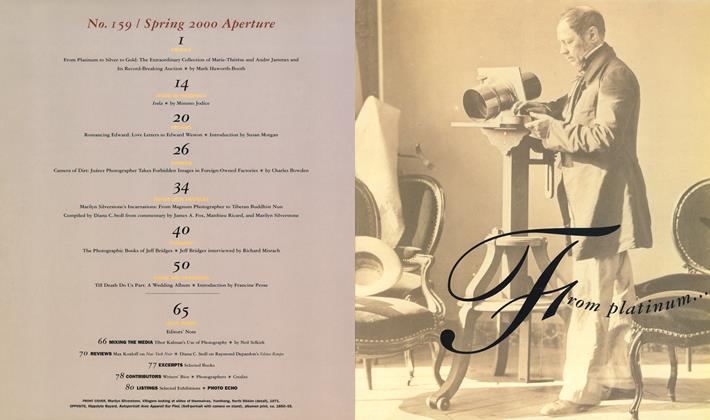

ProfileFrom Platinum...To Silver To Gold

Spring 2000 By Mark Haworth-Booth -

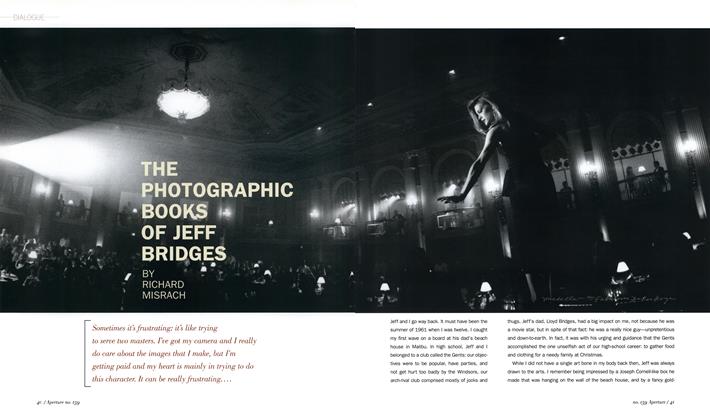

Dialogue

DialogueThe Photographic Books Of Jeff Bridges

Spring 2000 By Richard Misrach -

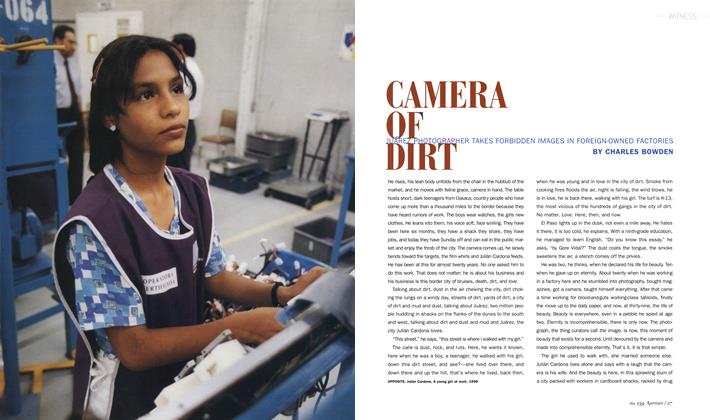

Witness

WitnessCamera Of Dirt

Spring 2000 By Charles Bowden -

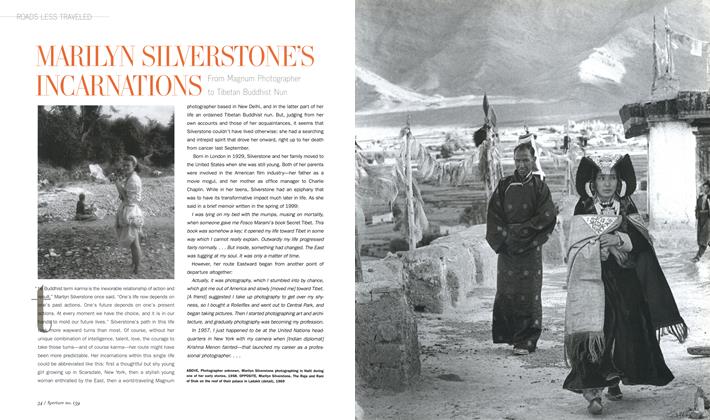

Roads Less Traveled

Roads Less TraveledMarilyn Silverstone’s Incarnations

Spring 2000 By Diana C. Stoll -

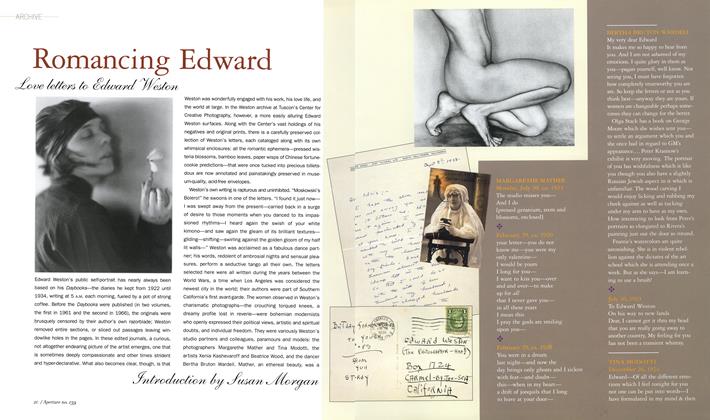

Archive

ArchiveRomancing Edward

Spring 2000 By Susan Morgan

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Mixing The Media

-

Mixing The Media

Mixing The MediaSara Vanderbeek Compositions

Spring 2011 By Brian Sholis -

Mixing The Media

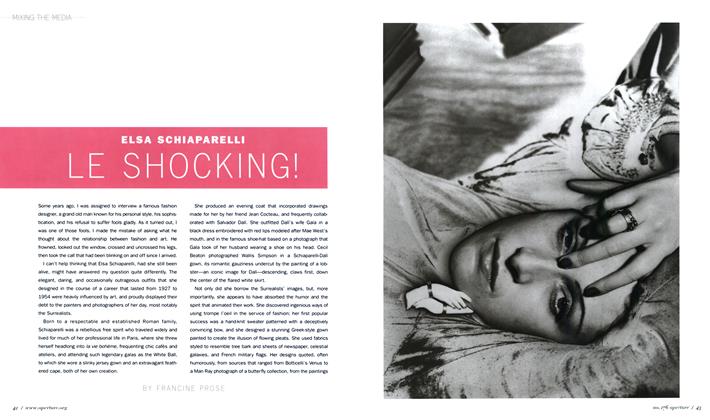

Mixing The MediaElsa Schiaparelli Le Shocking!

Fall 2004 By Francine Prose -

Mixing The Media

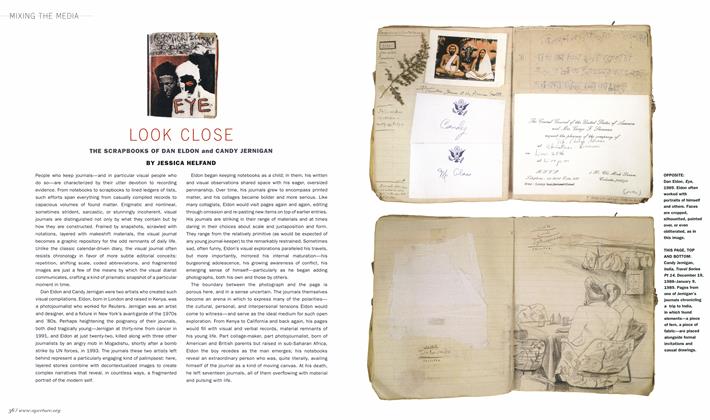

Mixing The MediaLook Close The Scrapbooks Of Dan Eldon And Candy Jernigan

Spring 2009 By Jessica Helfand -

Mixing The Media

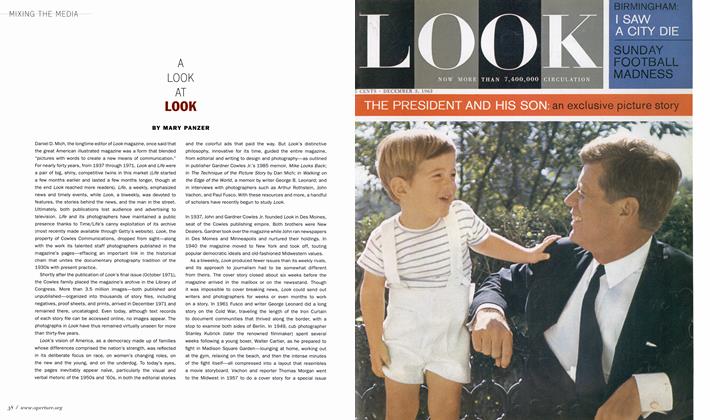

Mixing The MediaA Look At Look

Summer 2009 By Mary Panzer -

Mixing The Media

Mixing The MediaNew Style Sacred Allegory The Video Art Of Shirin Neshat

Spring 2002 By Minna Proctor -

Mixing The Media

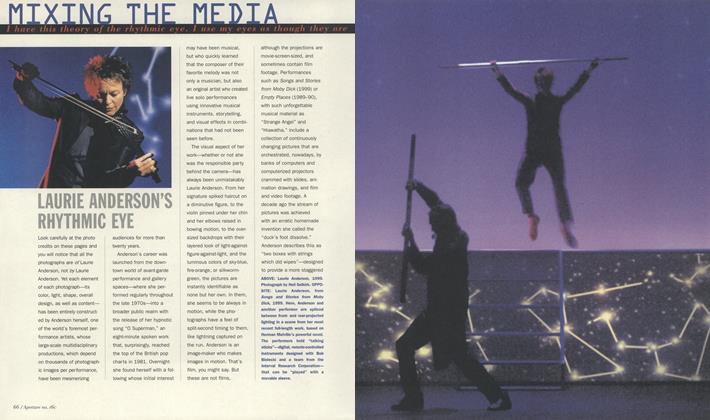

Mixing The MediaLaurie Anderson's Rhythmic Eye

Summer 2000 By Roselee Goldberg